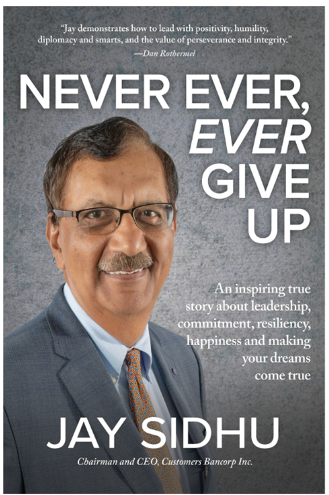

Never Ever, Ever Give Up

As a young man who grew up in India, Jay Sidhu backpacked across Afghanistan, Iran, and Western Europe with just $100 — managing to make it to London and back to India. He then moved to the United States with no money, connections, or friends. Sidhu is now CEO of Customers Bancorp, Inc.

Never Ever, Ever Give Up details Sidhu’s American dream journey — from having just two suitcases, starting higher education in America, and to leading a Fortune 500 company. His memoir not only touches on his experience in banking but also hits on his experience raising a family, leadership tips, personal philosophies, and more.

Never Ever, Ever Give Up has everything you could ever need to follow your dreams.

Are you ready to begin your journey to success, making your dreams come true?

Read Never Ever, Ever Give Up today!

Charities and scholarship organizations:

About the author Jay Sidhu

Jay Sidhu serves as Chief Executive Officer of Customers Bancorp, Inc., and Executive Chairman of Customers Bank. He has an extensive and recognized background in banking. Prior to joining Customers Bank, he served as the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Sovereign Bancorp, Inc. There, he grew the organization from an Initial Public Offering of $12 million to a market cap approaching $12 billion, crediting it as the 17th largest banking institution in the country.

Sidhu has received various recognitions in the industry, including Financial World’s CEO of the Year, Turnaround Entrepreneur of the Year, and was named the Large Business Leader of the Year by the Chamber of Commerce. He has spoken at YPO Universities in Dubai and Hong Kong about Authentic Leadership and has also been a speaker at conferences around the world including Singapore, London, Sydney, Prague, Dubai, and all over the US.

Sidhu earned a Master of Business Administration from Wilkes University and graduated from the Harvard Business School’s Leadership Course for CEO’s.

Follow Jay

Praise for Never Ever, Ever Give Up

An inspirational story about a first-generation immigrant rising to become a Fortune 500 CEO, raising emotionally healthy and successful children, and sharing his philosophy of humility, gratitude, authenticity, and happiness. A must-read for all, including all parents.

This book brings the American dream to life! A fascinating story about leadership, authenticity, commitment to values, and beliefs about free enterprise and what America offers to those who have a vision — and never ever give up.

— Jay Sidhu

Must Read Excerpts

Escaping Death During the Partition of India

On August 14, 1947, just a few months after they were married, my Dad rushed home. When he got there, he said to my mom, “We’ve got to get out of here!”

After some three hundred years in India and eighty-nine years of official colonial rule, the British Empire (or British Raj, as the UK’s government in India was called) was finally giving India back its independence. India was being partitioned, and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan was created for the Muslim minority.

That led to a massive political and religious split. People were separated on the basis of religion, a division that had been growing for decades in India under the British and really boiled over during World War II.

The Partition of India saw some of the most horrific violence of the twentieth century—there were mass rapes, abductions, dismemberment, and murder on both sides on a genocidal scale. Villages were set on fire. Millions of people—including pregnant women and children—were killed.

There was no law and order. Most people who lived through that deadly, terrible time in India don’t want to think about it today. I’ve spoken to many different people—my friends’ parents, and my mom and dad’s contemporaries—who lived in India and Pakistan then. They may talk a little bit about that time, but then they want to move on. They don’t want to dwell on it.

The Partition of India brought about one of the largest mass migrations in human history. Over six million Muslims went from India to Pakistan, and millions of Hindus and Sikhs moved from West Pakistan to India. About 12 million people were displaced amid the ensuing violence. Pakistan’s leaders essentially said, “Get rid of anybody in Pakistan who is non-Muslim. If they don’t want to go, convert them. And if they don’t want to convert … kill them.” On the other hand, India became a secular country. (In 1976, the 42nd Amendment to the Indian Constitution explicitly asserted India’s secularism.)

As the horror began, word came from Dad’s headquarters that trouble was on the way and that it was the responsibility of his battalion to make sure that all non-Muslims, including Sikhs like him and my mom, were protected. The officers in Dad’s unit basically told the non-Muslims that the situation was unfortunate, but they had to get out immediately.

Mom and Dad, who were on the other side of the area of what was now Pakistan, left on a train immediately to get to the Indian border, part of the mass migration out of the Muslim territory. At the time, my mom was a naïve seventeen-year-old girl who had never been out of India.

Mom described to me how she saw blood and bodies everywhere. She says she could never, ever forget that. But she says that on the train, my dad said to her, “Don’t worry about anything. Go to sleep, get some rest. My army colleagues and I are here to protect every family, everybody here. We will do anything and everything to make sure we get safely across the border into India.”

My parents were on the train all night. Everywhere in Pakistan, Pakistani soldiers and civilians were stopping transports filled with non-Muslims; they were boarding the trains and killing people. Because of the danger, every time my parents’ train slowed down during the night, my dad and the other soldiers around him would jump up with their guns.

Then suddenly, in the early morning hours … the train stopped.

My dad and his fellow soldiers used signal communications with walkie-talkies to talk to the other officers in the other sections, so they knew something was happening on both ends of the train. There were violent massacres in the train cars in front of and behind the car my parents were on. The Pakistanis went from car to car, and if the train didn’t move soon, the people in the middle section—including my mom and dad—would likely be killed.

Road Trip: India to London on 100 Rupees

What could be more exciting and pleasurable than traveling across Europe and Asia with your college friend, when you’re just 18 years old? When we think about visiting cities like Teheran, Istanbul, Athens, or London, we imagine ourselves staying in youth hostels or inexpensive hotels, meeting lots of other people our age, going out for great meals, and relying on train passes to get from one city to the next.

Now imagine the same trip, but this time without money, without youth hostels, without hearty meals, and without train passes. Instead, you’re hitchhiking mainly with truckers, sometimes for days at a stretch. You’re barely eating because you’ve got exactly $100 in your pocket, and it has to last for the entire trip, from Kabul, Afghanistan, all the way to London and back to India. You’re sleeping on the ground or on the sidewalk, not on beds with fresh linen, to save money, curled over your backpack to ensure that your clothing and worldly goods aren’t stolen. Train passes? Forget about it!

This is how Gautam, a classmate and friend at Banaras Hindu University, and I crossed from India to London when I was just 18 years old. We were naïve about the dangers, but somehow, we were protected, even when our lives were threatened on a dusty road in Afghanistan, and we found ourselves in jail in Paris. But somehow it all worked out and we had the adventure of a lifetime. That trip gave me the courage to pursue my dreams in life, to come to America and study, and to make something of myself. I’d like to invite you on that journey 50 years ago, when my friend and I set out on a mission to spread the idea of international peace and understanding.

The rare meal of bread with butter was a huge treat. I was terrified much of the time, and often, I was lost. But on occasion, I met kind people who generously helped me; many were simply trying to survive themselves, but they still shared with open hearts.

If I had known the difficulties and dangers ahead, it’s doubtful I would have left India and hitchhiked across continents. But I am so very, very glad I did. I discovered the excitement of taking risks and achieving extraordinary outcomes. I gained the confidence and sense of invincibility to confront challenges and overcome them. I became motivated to literally expand my horizons and travel abroad. And I learned that I was adaptable and resourceful.

My experiences also taught me that my father, whom you’ll meet in these pages, was right – by defining a mission and setting forth a step-by-step strategy to achieve it and even exceed expectations, I could succeed in life. I’m sharing these memories so that they might inspire you to take some chances and succeed in ways you might never have imagined!

Meeting with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi

Who would have thought that our meeting with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in Delhi would lead us to a meeting with prominent businessmen in Teheran? Or that the hug from the Prime Minister would be a prelude to their handshakes?

The interim step leading to the business meeting occurred at the Indian Embassy in Teheran. After a restful night at the Sikh temple, Gautam and I walked around city, and I was struck by how developed and Westernized it was. The women wore skirts, not burkas, and the roads had cars, not pedestrians. Teheran at that time (the Shah of Iran days) seemed so advanced that I felt as if I was already in Europe. Gautam and I walked purposefully to the Indian Embassy, unencumbered by our knapsacks.

We met the military attaché who happened to be acquainted with my dad, which was an encouraging coincidence. In conversation, I informed him of my affiliation with Rotary International, a service organization with the mission of effecting positive changes globally through a network of community leaders, businesspeople, professionals, and even kids like me. Their motto is “Service Above Self,” which was somewhat ironic since the Rotarians were instrumental in helping me achieve my personal mission to travel across continents.

The attaché had unexpectedly good news for us. He had once been a guest speaker for the Rotaractors, and they were meeting right now at the Royal Teheran Hilton Hotel. He immediately picked up the phone and asked his contact if he could send over two young Indian Rotarian guys to talk with the group. We couldn’t believe we had traveled from the dirt roads of Kandahar to a glass-and-steel luxury hotel!

Gautam and I wasted no time removing our UN and Indian flag pins from our knapsacks to wear proudly on our chests. Outfitted in a relatively clean checkered shirt, jeans, and comfortable suede shoes, I rode up five floors in a modern elevator and went into an equally modern conference room with an expansive view of the highway below. The room was set up like a boardroom, with a large oval-shaped table seating about 25 people. Everyone looked very businesslike and official in their sharply tailored Western suits and ties.

Never shy, I spoke on behalf of Gautam and myself, introducing us as the Rotarians referred by the military attaché at the Indian Embassy. We were asked to wait until their regular meeting concluded. That gave me some time to calm my nerves before one businessman asked me to explain why we were there. This was the first time I’d ever spoken to businesspeople outside of India (it would be the first of countless times during my career). Remember, I was just a college kid with long hair tied in a bandana and not-so-clean jeans. But I’d spoken to Prime Minister Gandhi, so this should be a piece of cake. I was rarely at a loss for words.

An Answer to a Letter: Acceptance to an American Graduate School

My plan to study in America took root when I was in eighth or ninth grade. My cousin Sher, who was about 20 years older than me, and my older brother Harry were my role models. My cousin emigrated to America and studied engineering at the University of Michigan, which has a very competitive, highly ranked engineering program. He visited my family on one of his trips back to India, and that was a pivotal moment in my thinking. I was entranced by my cousin’s description of how he managed to board a ship to America and made his way to university. Later, he became a successful self-made man. At a young age, I was determined to be like him. Specifically, I was determined to follow his footsteps across oceans and create my own story of business success.

I was also inspired by my brother, who managed to reach the US to study mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan. He had no money and worked eight-plus hours a day at odd jobs like standing in front of a scorching-hot oven baking pizza while he went to school. He did whatever it took, and I would too.

… I scoured all the thick, encyclopedic books in the library with detailed descriptions of US universities. I identified the primary criteria for schools to maximize my chances of acceptance: schools without a stringent requirement for the ATGSB. Ones that offered financial aid to international students. And smaller, less competitive schools that would be more likely to read my letter. I was realistic but couldn’t resist applying to the Ivies – Penn, Columbia, and Stanford. After compiling a list of universities, I launched my plan of attack: a letter-writing campaign.

Yes, good old-fashioned letters on cheap aerogrammes of tissue-thin paper with cheap postage that you folded and sealed to form a letter. I sent over forty letters! My gut told me that my admission chances were slim, even in 1971, but I was undeterred. Since my time was limited, copy machines weren’t available, and I was a poor typist, I used carbon paper to type three letters at a time. My approach was systematic: the originals went to the best schools, the copies to others.

The letters were sincere. I began with a humble apology, writing it may seem odd that I am sending this request for admission without filing a formal application. However, I wrote, I can’t afford the graduate school application fees. I explained that I was hard-working and resourceful. Hopefully, that was implied by the very fact of my letter. Further, I explained my unwavering passion to attend university in the United States and earn an MBA. I promised that once I’m successful, I’m committed to giving back my good fortune to the school and to society, in appreciation of my excellent education. I made good on my promises, which you’ll learn about later. I expressed my commitment to promoting international understanding. If you give me a chance, I wrote, I’ll pay it forward. I also included personal information – a kind of resume that we then called biodata – about myself, my extracurricular activities, and grades in the letters.

And then, I dreamed and waited.

Of the forty schools I wrote to, I heard back from two with admissions offers: Andrews University (a Seventh Day Adventist school) in Michigan and Wilkes College (now Wilkes University) in Pennsylvania. A five percent response rate. Not a bad return on my paltry investment in flimsy aerogrammes and carbon paper. There was a problem: neither Andrews nor Wilkes offered me financial aid. Or so I thought.

I reread the Wilkes letter written by the dean of students, George Ralston, which had included an I-20 admission form for foreign students. And then, I saw it! The dean actually did say the university would award me a full scholarship and free housing in the dorm. Wow! Another good return on my investment! Wilkes asked for additional information like letters of recommendation, which I wasted no time providing. I was fortunate and grateful and convinced that my acceptance reflected the kind of country America is – a compassionate land of opportunity.

My Night in a Paris Jail

Now here’s another first I experienced on this trip: a night in jail.

The jail’s superintendent was a man in his forties from Africa’s Ivory Coast, a very tough guy. Completely bald. In broken English, he asked us what had happened. We explained our peace mission and told him we were military officers’ children, and please, please, we needed to get to the Indian Embassy. The cop was sympathetic – I think he’d had a tough time coming to France and understood what it was like to be different and look different.

He apologized to us, saying that it was unfair we were arrested. Unfair that people like us who were trying to do good were misunderstood. And he felt so badly jailing us that he left the doors to our cells open. That way, he explained, we wouldn’t feel too afraid. It was a city jail, but nobody was in any of the half-dozen or so tiny cells that day, so he gave us separate cells. He assured us that we’d be taken to the Indian Embassy in the morning. Despite the cold concrete floor, we slept pretty well.

I’ll never forget the superintendent’s compassion. The only thing was, he was required to keep our passports while we were in jail.

When we got up in the morning, the cop from the Ivory Coast had left a note for us. Now we just wanted to get our passports back. We didn’t care about anything else. The new cop on duty was French and didn’t speak much English and seemed to have difficulty locating our passports. We were still scared—what if they charged us for trespassing or something even more serious? But he found our passports, gave them back, and then put us into a police car to be taken to the Indian embassy.

At the Indian embassy, we were brought to the military attaché for the government of India. And wouldn’t you know, the military attaché just happened to have a friend in common with my dad! It’s such a small world.

We learned that the cop from the Ivory Coast had done us another kindness the previous night. He had contacted the Indian Embassy to verify our story and make them aware of our situation. When we arrived at the embassy, everything was already sorted out. The officials wanted me to try to reach my dad, but he was stationed at a post in the mountains in Northeast India, and I couldn’t reach him. Nevertheless, the embassy took care of everything, and we spent the day pleasantly walking around Paris.

A Bank CEO at 38

At age 38, I became CEO and president of both Sovereign Bancorp and Sovereign Bank in 1989. In roughly four hundred days, we did it: We turned Sovereign into a well-capitalized, billion-dollar-plus bank.

Among my other strategic initiatives, we embarked on opening new branches and making new acquisitions to build revenues that were twice our overhead expenses. We identified problem banks to buy cheap and turn them around. Unlike the days before statewide and interstate banking, we were no longer limited to contiguous counties. So New England, the mid-Atlantic states, and elsewhere were fair game.

Our first major acquisition was a small institution in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, called Yardley Savings and Loan. Like every new company Sovereign acquired after that, whenever appropriate, the acquisition would preserve its name, management, and place in the community. Having rid ourselves of our bad loans, the bank’s expansion was gaining forward momentum. This is remarkable – when the US was experiencing the S&L crisis, we were strong and opportunistic. While other S&Ls were struggling and failing, we were building a highly successful bank.

I endeavored to create a corporate culture of not only institutional improvement but also personal growth. I was so committed to the principles I learned in my professional development seminars that I made attendance at a Dale Carnegie course a requirement for everyone in a leadership role. Additionally, I held leadership to a high standard of operational excellence and integrity.

Forced Out at Sovereign – Beginning of Customers

My foray into the private equity financial sector had confirmed it wasn’t my forte; banking was my passion. I thrive on turning around failing banks and running them successfully and profitably. Unfortunately, Ralph Whitworth from Relational Investors had tried to impugn my character. But despite the debacle that ensued when I was forced out of Sovereign Bank, I never gave up. Instead, I was resilient. That experience served to magnify my drive to restore my reputation and invigorated my passion to return to the banking world. My friend Dick Ehst and others encouraged me to undertake a leadership role again. Not just encouraged me; they said they’d join me.

Although it was 2009, a new century beckoned!

Ken Mumma was the Chairman and CEO of New Century Bank, headquartered in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, and worked with his wife Moira Forbes. Sadly, while dating Moira, Ken was in a car accident that left him paralyzed from the waist down. He’s a very respectable, smart guy, but simply couldn’t put 100 percent of his energy into New Century Bank. So he hired the head of private banking for CoreStates Bank to run it as its president. This individual tried to use private banking approaches with the customers, skilled trade entrepreneurs like plumbers and electricians, and the bank got into big trouble. Ken blindly trusted the president he’d hired and couldn’t clearly see the mismanagement plaguing the company.

Several factors appealed to me about the opportunity to tackle and transform New Century Bank: working with Ken, staying in the Pennsylvania area near Sovereign, and, best of all, a golden opportunity to make a small bank into a robust financial entity. Ken and I talked frankly about the situation, and I asked him to give me a week to diagnose the bank’s ailments and prescribe a cure.

It may seem counterintuitive, but running a small bank is much more challenging than running a large one. The leadership needs to worry about every detail and every dollar, and banking is highly regulated by the US government. Several supervisory bodies oversee the financial industry, including the Federal Reserve Board (FRB), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC), the State Department of Banking, and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). So before I invested time and money, I talked to the regulators and conditioned my investment on their allowing me the chance to acquire any failing banks in the area. They agreed, and we made a deal!

I did my homework and spent 12 plus-hour days at the bank. Driving home through Pennsylvania’s country roads, I calculated that New Century was losing an average of $12 thousand a day! I’d never before had brackets indicating negative numbers on an income statement. This was serious!

I enlisted several former Sovereign colleagues and trusted friends, including Dick Ehst, to collectively invest $17 million with me in New Century. And with Dick’s invaluable input, I put together a plan. I told Ken that the current president had to go, and I needed to bring in my own management team. Ken heartily endorsed the arrangement and remained a director while I became chairman and CEO. He also agreed to bring in Dick as president and COO.

We engineered a three-pronged strategy that was well executed by our highly qualified and experienced executive team. To make New Century healthy, we proposed amassing a variable rate, high-quality loan portfolio that would: (1) generate revenues, (2) cut costs and make the bank more efficient, and (3) fix the loan problems ASAP. We launched a new mortgage warehouse division, spearheaded by Glen Hedde, to bring in high quality variable rate loans quickly to build the revenue stream. Mortgage warehousing provides short-term funding to loan originators. The underlying mortgages are then sold by the originators on the secondary market. This financing enabled the bank to develop expertise in a niche that provides solid recurring revenues from high quality loans and fees.

Bringing My Children into Banking

When my daughter Luvleen was studying for her bachelor’s degree at Harvard University, she came to me with a brilliant idea: to incubate a consumer bank that attracts college students by using digital technologies like smartphones and tablets. Tapping this young market was effective for many reasons, and students generally stick with their first bank for life. (I still use the VISA credit card issued to me as a student!) Luvleen subsequently earned an MBA at The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

The result of Luvleen’s entrepreneurial vision was BankMobile, which partners with universities and large businesses to help market and support their products. Then Customers Bank spun off BankMobile to become BankMobile Technologies, which went public in 2021 – its symbol on the NYSE is BMTX. BankMobile was the first bank in the US to wipe out overdraft fees, bringing the attention of the public to an industry-wide problem: banks were charging billions of dollars of fees each year that not only cost consumers but yielded inefficient branch returns. Now, “the big four banks” (Bank of America, JP Morgan Chase, Wells Fargo, and Citibank) are following suit. This no-fee policy reflects the trend to accelerate the closing of bank branches. Why? They depend on high fees to cover their excessive real estate, personnel, and other ancillary carrying costs.

While BankMobile Technology focuses on consumer banking, Customers Bancorp concentrates on business banking. When I was in my 60’s, I had no plans to retire. But I did want to think about succession planning for Customers. Our board takes corporate governance very seriously, and they also thought it prudent to bring someone new onboard. Dick was in charge of the search and hired a recruitment firm to look both internally and outside the organization for his and my successors. Our primary criteria were to find tech-savvy leaders with significant experience in the financial services industry who shared our vision and values – someone capable of leading Customers for the next couple of decades.

Dick announced at a board meeting that he’d found an ideal candidate: Sam Sidhu. I was flabbergasted at the suggestion that my son take over. Yes, Sam was well-educated – a Wharton School degree in economics and a Harvard MBA. Yes, Sam was trustworthy, and his values and vision were compatible with ours. Yes, he had a stellar resume. But there was one pitfall. Sam had founded his own private equity firm, Megalith Capital Management in New York. I felt sure Sam wouldn’t leave the firm he’d established with a Harvard classmate over 10 years ago. He was as passionate about his work as I was about mine!

The Road To Bethlehem And A Banking Career

A detour on the road to Bethlehem led to my banking career! No, not Bethlehem, Israel. It was an exit off the Pennsylvania Turnpike to Allentown and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

In the spring of 1973, toward the end of the second and final year of my MBA program, corporate recruiters visited the Wilkes University campus. Although the economy was in a recession, companies were tempting us students with promises of money, status, and opportunities for career advancement. Among the companies I interviewed with were Travelers Insurance and Sylvania Electronics, and I enthusiastically accepted a job with the latter. My first full-time job in America!

Shortly after accepting the job offer, I visited the office of Dr. Warner, Dean of the Department of Commerce, to chat and share my news. Ultimately, the meeting would demonstrate the value of networking. Dr. Warner said that he and Dr. George Ralston, Dean of Students, had bumped into Wilkes’ chairman of the board of trustees, Reese Jones, the CEO at First Valley Bank in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Mr. Jones had asked the deans to recommend a student for a job at the bank, and my name rose to the top of the list.

Dick Ehst, an executive at First Valley and a friend of Dean Ralston, had researched and recommended me to him. Dick later told me about the call he had received from Dean Ralston about a “very special aristocratic Indian” he must interview.

Dick is a brilliant guy, who became a valued mentor, and later, a great friend and a trusted colleague. He continued working with me when I became chairman and CEO at Sovereign Bank and Customers Bank. I explained to Dr. Warner that I’d already accepted a job at Sylvania, but Dr. Warner asked me to do him a favor anyway and see Dick and Mr. Jones at their office in Bethlehem.

I didn’t pursue the matter then, but the Pennsylvania turnpike exit beckoned. On my way to visit my brother Harry in Philadelphia, I impulsively took the Allentown/Bethlehem exit and found myself at the main offices of First Valley Bank at 535 Main Street. I became a bit flustered because I couldn’t remember the name of the bank president Dr. Warner wanted me to see. Undeterred, I nonchalantly asked a secretary. Also, I didn’t have an appointment with Mr. Jones. On top of that, I was wearing jeans, a t-shirt, and long hair, the typically scruffy uniform for university students in the 60s and 70s. My appearance certainly wasn’t appropriate for a business interview. Nevertheless, Mr. Jones’ assistant ushered me into his office. She later told me she had thought that I was a friend of Reese Jones’ son, which was a lucky mistake for me.

Mr. Jones and I exchanged pleasantries, and he asked about my background. As usual, I had plenty to say and animatedly described my upbringing, hitchhiking adventures, and classes. The conversation shifted to the topic of banking. Mr. Jones began discussing the restrictive nature of banking at the time. He explained that you had to stay in your local county or the contiguous counties to open new branches. I wasn’t sure where the conversation was heading, but Mr. Jones continued. He asked the question that led to my job offer: how do you think the bank can overcome this geographical obstacle and open more successful branches? I suggested we analyze the successful existing branches to figure out what three or four things make them work well. Then, I continued, we consider a similar model whenever we look at a potential new location.

I had a 4.0 GPA at Wilkes, and I aced this interview too. Mr. Jones hired me on the spot. However, I thanked him for the kind offer and told him I’d already accepted a job at Sylvania. Now it was his turn not to be deterred. He said, “Look, you haven’t started there yet. Whatever Sylvania is paying, I’ll pay you $500 more.”